“The universality of tattooing is a curious subject for speculation….” Captain James Cook recorded in his journal during his third Pacific journey from 1776 to 1780. While the practice of tattooing had been ongoing in indigenous cultures for thousands of years, Cook and Royal Navy sailors who observed the Polynesian body art were among the first to bring the practice of tattooing back to Europe and America.

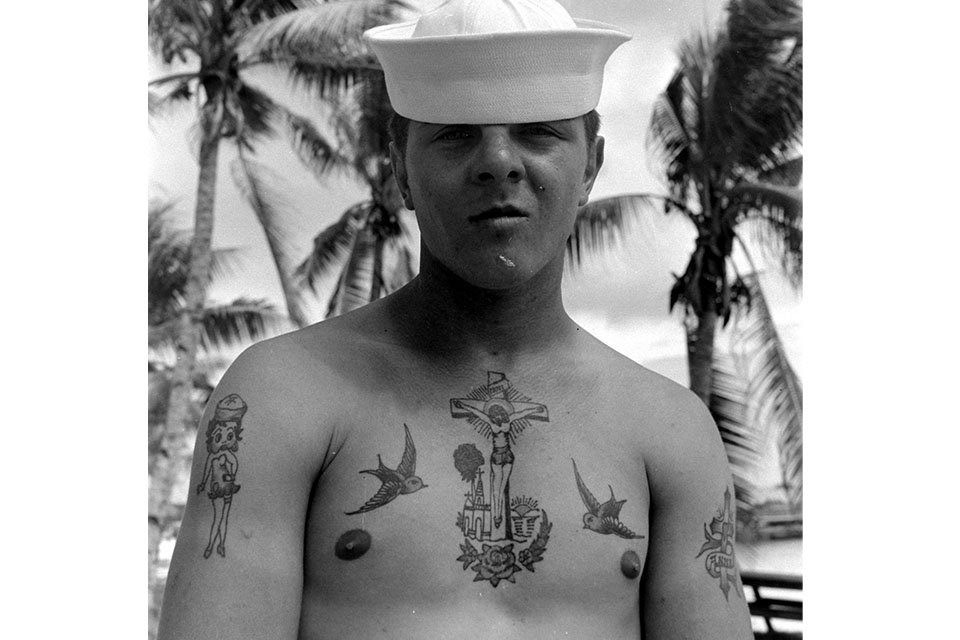

Bored sailors turned amateur tattoo artists began to dabble in putting ink to flesh, the most common being military insignias and the names of sweethearts back home — naturally the mark of a great, lasting relationship.

The practice quickly spread across the fleets.

According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, “by the late 18th century, around a third of British and a fifth of American sailors had at least one tattoo.”

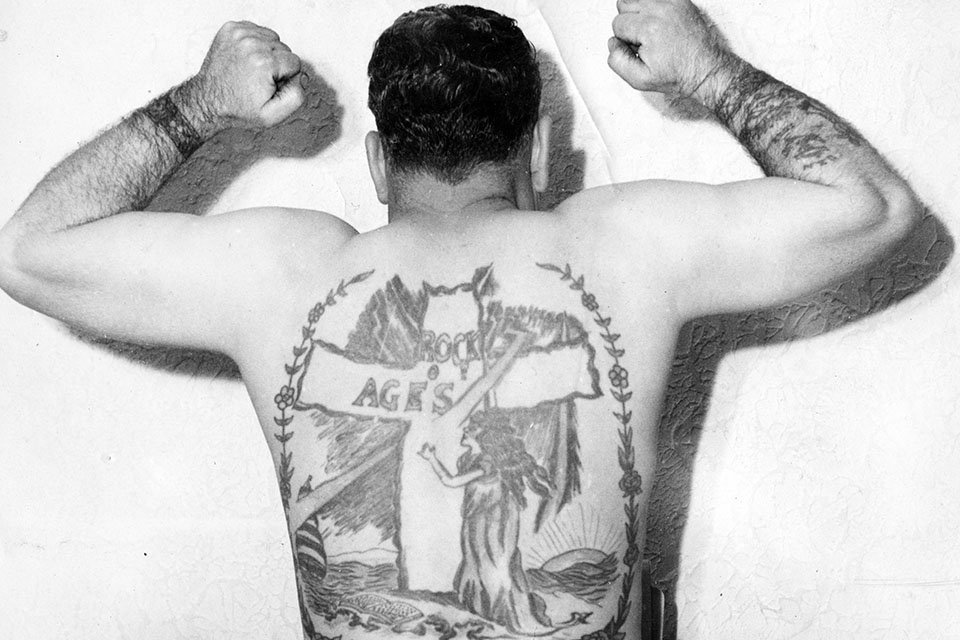

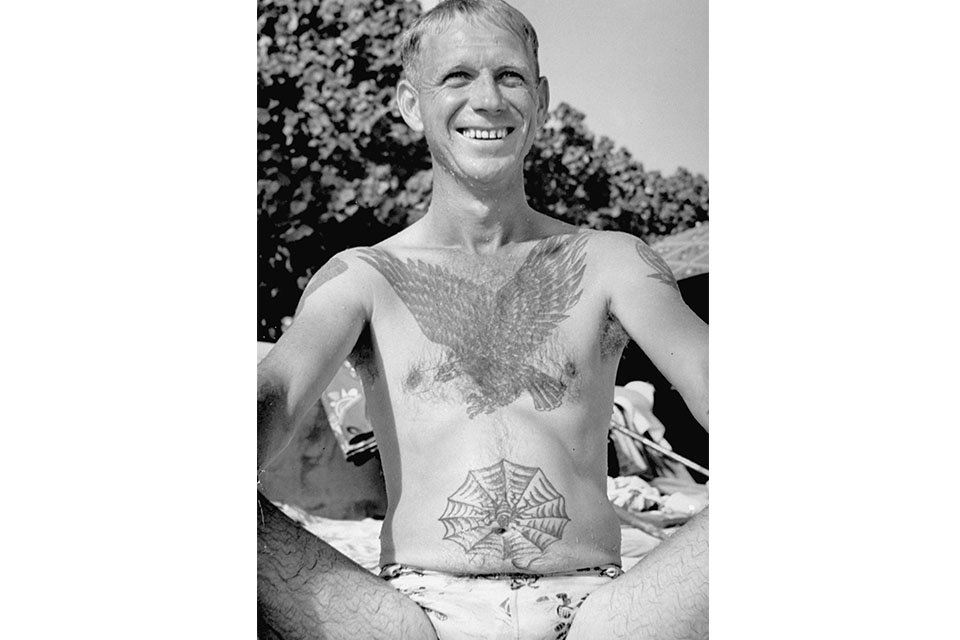

Since Cook’s journeys, shellback turtles, swallows, ships, anchors, daggers piercing a heart, and more continue to “memorialize special memories or career milestones at sea, such as crossing the equator or eclipsing 5,000 nautical miles for the first time,” writes J.D. Simkins of Military Times.

Despite tattoos being a well-established Navy tradition, sailors adorned with tattoos were still considered fringe or “unsavory” members of society until the mid-20th century.

During World War I sailors were highly encouraged to cover up any risqué body art since any perceived “moral” failings might disqualify them from service, states the NHHC.

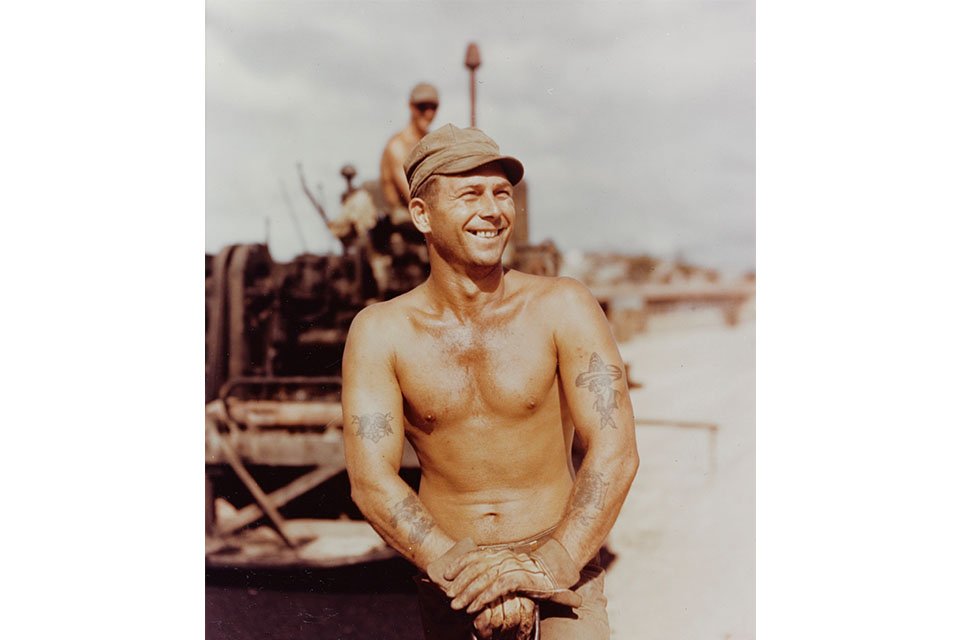

The onset of World War II, however, and the vast expansion of Naval personnel ushered in a new era of the tatted tradition, thanks in large part to artist Norman Keith Collins — also known as Sailor Jerry.

Since then, the Navy has been the most lenient among the other military branches in regard to its tattoo policy.

In a bid to recruit more sailors, the Navy eased its policy even further in 2016, allowing men and women to “have neck tattoos, sleeves and even markings behind their ears,” writes Mark Faram of Navy Times.

Some Traditional Sailors' Tattoos

Anchor: Originally indicated a mariner who had crossed the Atlantic. In the present day, an anchor in one form or another may be the first nautical tattoo a young Sailor acquires (often during his or her first liberty from boot camp) and is essentially an initiation rite into the naval service.

Braided rope/line: Usually placed around left wrist; indicates a deck division seaman.

Chinese/Asian dragon: Symbolises luck and strength—originated in the pre–World War II Asiatic Fleet and usually indicated service in China. Much later, dragons came to symbolise WESTPAC service in general (also worn embroidered or as patches inside jumper cuffs and on cruise jackets).

Compass rose or nautical star: Worn so that a Sailor will always find his/her way back to port.

Crossed anchors: Often placed on the web between left thumb and forefinger; indicate a boatswain’s mate or boatswain (U.S. Navy rating badge).

Crossed ship’s cannon or guns: Signify naval vice merchant service; sometimes in combination with a U.S. Navy–specific or patriotic motif.

Crosses: In many variations—worn as a sign of faith or talisman. When placed on the soles of the feet, crosses were thought to repel sharks.

Dagger piercing a heart: Often combined with the motto "Death Before Dishonour"—symbolises the end of a relationship due to unfaithfulness.

Full-rigged ship: In commemoration of rounding Cape Horn (antiquated).

Golden Dragon: Indicated crossing the international dateline into the "realm of the golden dragon" (Asia).

“Hold Fast” or “Shipmate”: Tattooed across knuckles of both hands so that the phrases can be read from left to right by someone standing opposite. Originally thought to give a seaman a firm grip on a ship’s rigging.

Hula girl and/or palm tree: On occasion, hula girls would be rendered in a risqué fashion; both tattoos indicated service in Hawaii.

Pig and rooster: This combination—pig on top of the left foot, rooster on top of the right—was thought to prevent drowning. The superstition likely hearkens back to the age of sail, when livestock was carried onboard ship. If a ship was lost, pigs and roosters—in or on their crates—floated free.

Shellback turtle: Indicates that a Sailor has crossed the equator. “Crossing the line” is also indicated by a variety of other themes, such as fancifully rendered geo-coordinates, King Neptune, mermaids, etc.

Ships’ propellers (screws): A more extreme form of Sailors’ body art: One large propeller is tattooed on each buttock (“twin screws”) to keep the bearer afloat and propel him or her back to home and loved ones.

Sombrero: Often shown worn by a girl. May have indicated service on ships home-ported in San Pedro (Terminal Island, Los Angeles) or San Diego prior to World War II, a liberty taken in Tijuana, or participation in interwar Central and South American cruises.

Swallow: Each rendition originally symbolised 5,000 nautical miles underway; swallows were and still are displayed in various poses, often in combination with a U.S. Navy–specific motif or sweetheart’s/spouse’s name.